4.1 Web and Service Workers

# Asynchronous vs Synchronous

JavaScript has a mechanism known as the event loop. When you pass a list of commands to the event loop, it will keep running each of those commands in order until it gets to the end of your list. This list is known as the main stack. JavaScript keeps trying to run commands as long as there is something on the main stack.

However, sometimes there is a command that would stop the event loop from getting to the next command. It gets blocked from going to the next command in the stack. These types of commands are things that take a long time to complete, like talking to a database, or the file system, or a network request for a file, or a timer that needs to wait before running.

There are specific tasks that are going to take too long and they get put into a secondary area so they can wait for their result. These tasks are known as asynchronous.

If the code stays on the main stack and insists on being run before the event loop moves on to the next item then it is called synchronous.

# Core JavaScript VS. the Web APIs

The JavaScript that we use in the browser is actually made up of two different things.

There is the Core JavaScript that we were using with Node.JS for the first few weeks of the semester and there are the Web APIs.

The Core part is made up of the features like variables, if statements, functions, data types, arrays, loops, ternary operators, the Math object.

The Web APIs are all the things that are added on top for the browser - HTML DOM, CSS style manipulation, handling AJAX requests, timers (setTImeout and setInterval), the browser events, geolocation, local storage, and all the features added to support mobile devices.

What is the difference between synchronous and asynchronous JavaScript? Watch this to see:

# The JavaScript Loop

The JavaScript engines, like Chrome's V8, use a single thread to process all your code. It builds a stack of commands to run, in the order that you have written them. As long as each command belongs to the CORE JavaScript then it gets added to the main run stack.

When something that belongs to the Web APIs is encountered it gets added to a secondary list of tasks. Each time the main stack is finished then the JavaScript engine turns it attention to the secondary list of tasks and will try to run those.

Here is a great video that explains how the JS Event Loop works.

# Async Await

When you call an asynchronous method like fetch, loading an image, timers, getting geolocation, talking to a database or reading a file, then we need to handle this in our code. Most asynchronous tasks have a callback method that we can use. Another approach we can use is wrapping the task inside a Promise and then using a then().

If you want to use the Promise version but want to simplify your code then we can use the keywords async and await.

One of the features added in ES6 was async and await. The combination of these keywords lets us use asynchronous features like fetch inside a function but in a synchronous way.

Here is an example.

async function getData() {

let url = 'https://www.example.com/items/';

let response = await fetch(url);

// now we have the actual response object in our response variable

let data = await response.json();

// now we actually have the JSON data inside the data variable

console.log(data);

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

This works by wrapping the asynchronous call in a Promise and making the rest of the function wait for the result before continuing. Without the await the variables response and data would not work properly. response would hold the Promise object which is the fetch waiting for a response. The next line, where we call the json() method would fail because that is not a valid method to call on a fetch or promise object.

The await is what solves the problem and makes the code wait for the result of the fetch() and the json() methods.

Here are a few videos about Async Await.

# Shared Web Workers

By now we are very familiar with the idea that JavaScript runs the main stack on a single thread. This means that the main stack runs in a synchronous way - one task at a time.

We do have asynchronous things like Events, Timers, and Promises which will be placed on another thread to be handled. When they are ready to be used they get put in a queue to wait to be added back onto the main stack. They can only be added back onto the main stack when it is empty and all the current tasks are complete.

So, if you have a processor intensive task to complete but it isn't connected to a Promise, Timer, or Event then you are stuck with the main stack not able to do anything until it finishes this big task. Updating the interface and interacting with the user in a real-time way could be jeopardized.

The solution? Shared Web Workers. With these, we can actually create our own new thread to use and run our complex task on that other thread. Our main stack will, once again, be free to work with the interface and the user.

Shared Web Workers can contain practically any code we want, except it is not allow to access the DOM (the interface).

# Service Worker Intro

Here is a great article (opens new window) about the differences between Service Workers, Web Workers, and Worklets. All three are workers meaning that they get launched from a webpage script and they run on a separate thread to offload some processor intensive work.

Web Workers are just instantiated and run to off load a task.

Worklets are run to help us do things during the rendering process on the page. They do NOT have access to the DOM.

Service Workers get registered | installed and remain in the browser. They run in the background and act as a proxy server to intercept all the file requests that come from the browser. They can work with fetch, the cache API, and the indexedDB API to help you build offline first web apps. They do NOT have access to the DOM.

# Registering and Installing Service Workers

Registering a service worker for your website can be quite simple.

navigator.serviceWorker.register('/service-worker.js');

The serviceWorker object exists inside the window.navigator object. You can call the file that holds your service worker anything that you want but it should be saved at the root of your website.

When you register the file it will automatically be applied to EVERY tab and EVERY webpage under the current domain.

If you are working on a project that is running in Chrome under http://127.0.0.1:5500 and you register a Service Worker then it will remain there and apply to every webpage from http://127.0.0.1/ that you open on Chrome until you remove it yourself through the Chrome Dev tools.

If you want to see if a Service Worker is currently running for your webpage, you can use this:

let myController = navigator.serviceWorker.controller;

If there is an active Service Worker then it will be assigned to myController.

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) {

// Do a one-off check to see if a service worker's in control.

if (navigator.serviceWorker.controller) {

console.log(

`This page is currently controlled by: ${navigator.serviceWorker.controller}`

);

} else {

console.log('This page is not currently controlled by a service worker.');

}

} else {

console.log('Service workers are not supported.');

}

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

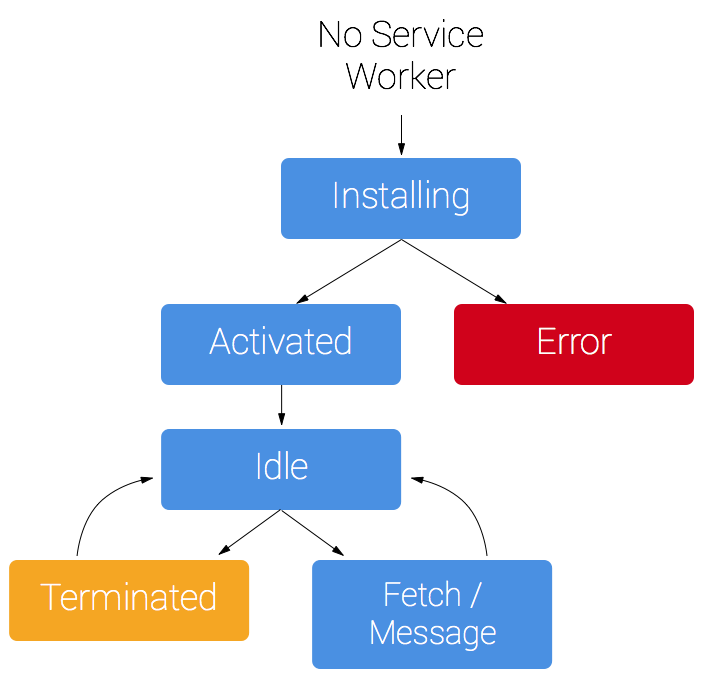

# Life-cycle for Service Workers

The life cycle for service workers has two critical events install and activate. When you call the register method for the service worker, the browser will check to see if this specific file has previously been installed. If not, then it will install it and trigger the install event.

If the file was previously installed but there is a change to the code inside the file then it will trigger a new installation of the script. Service workers are installed for a specific domain. They are tied to the current domain.

The activate event happens when a service worker has been installed and there is no other service worker currently running on any tab in the browser for the current domain. As long as there is still an older service worker running, the browser will not want to active the new file or new version.

If you load your webpage once and the browser installs and activates a service worker, then you edit the service worker and reload your webpage, the browser will install but NOT activate the new version because the older one is still active and running. Refreshing a second time will unload the old one and activate the newest version that is installed.

Once activated the service worker can handle events for fetch and messaging between the worker and the webpage.

The install event is the best time to create any new version of the file cache array that you will need for your new service worker.

The activate event is when you would delete old versions of the file cache.

If you want to update your IndexedDB then you can open the new version of the database from your activate event and use the upgradeneeded event to make any structural changes you want there.

Inside your Service Worker file you can add listeners for the install and activate events. The keyword self is used in the service worker script to refer to itself.

self.addEventListener('install', (ev) => {

//code to run when the install event happens

});

self.addEventListener('active', (ev) => {

//code to run when the service worker becomes active

});

2

3

4

5

6

7

Since, the manner in which cached files, database access, and fetch calls are handled, can be very sensitive to the specific version of the client side script in the browser we have to be able to manage the installing and activating of these shared service workers.

installing -> installed -> waiting -> activating -> activated -> idle -> stopped -> terminated

The idle phase happens when the webpage is still active but the service worker has nothing to do.

The stopped phase happens when the tabs for the current domain are all closed. The service worker is still registered and installed but it is dormant. Once another page for that domain is loaded, the Service Worker can become activated again.

The terminated phase happens when a service worker is unregistered | uninstalled. This must happen before a new service worker for the domain gets activated.

More reading on the lifeCycle (opens new window)

# Dev Tools for Service Workers

In Chrome, we can use the Application tab in the Dev Tools to find everything we need to work with Service Workers. Service Worker Registration, IndexedDB, localStorage, Cookies, Caches, Manifest, and Background Services are all found in this tab.

# Service Worker Playlist

Here is a whole playlist tutorial on how to build and use Service Workers.

Service Worker Playlist (opens new window)

The videos in the playlist are:

- Registration, Life-Cycle, Events, and Dev Tools

- The Cache API

- waitUntil, skipWaiting, claim

- How to integrate Caches

- The Storage API

- Controlling Fetch Calls

- When Fetch Goes Wrong

- Messaging Between Tabs and Service Workers

- Integrating a Database

# What to do this week

TODO

Things to do before next week

- Read and Watch all the course content for

4.1,4.2, and5.1 - Complete Hybrid 2